Parched Lands, Polluted Waters: East Africa’s Urgent Water Crisis

East Africa’s escalating water crisis poses a significant threat to human well-being and regional development. Since the 1970’s, East Africa has faced recurring disasters such as floods and droughts which have worsened over time with the added impact of climate change. As a result, about 40% of people in Sub-Saharan Africa have been left without clean water, with East African countries being among the hardest hit. Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia are some of the countries in the region experiencing water scarcity issues due to the increased unpredictability of weather patterns and intense weather events. The intertwined issues of water scarcity and deteriorating water quality have far-reaching implications for public health, food security, economic development, and political stability across the region.

The Current State of Water Resources

East Africa’s water resources are under severe pressure with Kenya reporting water availability of just 647 cubic meters per capita, below the water scarcity threshold of 1,000 cubic meters. Ethiopia faces similar challenges with approximately 1,200 cubic meters per person, which masks significant regional disparities due to still being below the Falkenmark Water Stress Index at 1700 cubic meters.

In addition to those concerning statistics, the region’s major water bodies indicate concerning trends. For example, Lake Victoria, Africa’s largest lake, has experienced fluctuating water levels attributed to climate variability and hydropower operations. This then ties to reports of increasing competition for these shared waters further highlighting the change being shown in water levels. This is also shown in a study that details alarming ecological changes in regional lakes.

Climate Change Impacts

Climate change acts as a risk multiplier for East Africa’s water challenges with projections indicating an increase in extreme weather events, including both prolonged droughts and heavy rainfall episodes on top of the regions aforementioned water availability. These drastic changes in weather events, a result of climate change, will only increase the rate at which the region’s atmosphere is sapping moisture from one region and feeding into storms elsewhere thus leading to an increase of weather-related disasters.

Rainfall patterns have become increasingly erratic, with the Greater Horn of Africa Climate Outlook Forum documenting shifts in timing and intensity of seasonal rains. This unpredictability directly impacts agricultural planning and water resource management.

Perhaps most visibly, Mount Kilimanjaro’s glaciers have lost over 85% of their ice cover since 1912, compromising a critical source for surrounding ecosystems and communities. These melting ice caps represent just one of many apparent manifestations of broader hydrological changes affecting the region.

Water Quality Challenges

East Africa faces a dual water crisis: scarce supplies and polluted sources. Research identifies poor wastewater discharge standards, weak monitoring, and financial shortfalls as major contributors to water pollution across the region. This has triggered an increase in heavy metal and bacteria content in waterways that exceed national and international standards.

A study found that toxic metals such as mercury, lead, and other harmful metals were found in soil samples collected from agricultural sites, with some samples exceeding the maximum permissible limits set by the World Health Organisation. If water run-off is not properly managed and accounted for, then these contaminated soils could end up in rivers leading to water pollution of fresh water sources.

In addition to contaminated agriculture sites, poor sanitation still remains pervasive. UNICEF reports that approximately 70% of East Africans lack access to safely managed and basic sanitation facilities. This contributes directly to water contamination and waterborne diseases like cholera, which continues to cause outbreaks across the East African region.

In coastal areas, saltwater intrusion also presents an emerging threat. As freshwater resources diminish and sea levels rise, saltwater is penetrating coastal aquifers, rendering them unsuitable for drinking or agriculture.

Human Factors Exacerbating the Crisis

Population growth places pressure on East Africa’s water resources with the region’s population expected to double by 2050 and urban centres growing particularly rapidly. Nairobi’s population alone is projected to reach 14 million by 2050, straining already inadequate water infrastructure.

Agricultural expansion, while necessary for food security, may account for a large percentage of water usage due to the region’s countries being agricultural dependent. Kenya, for instance, has 34% of its total gross domestic product and another 27% through linkages with other sections, tied to agriculture. Inefficient irrigation practices also contribute to water issues with the FAO estimating that up to 60% of water used in traditional irrigation systems is lost to evaporation or runoff.

Deforestation further disrupts hydrological cycles with Kenaya’s water towers, crucial forested highlands that capture rainfall and feed rivers, having lost at least a quarter of their coverage in recent decades. This degradation reduces water retention capacity and increases erosion, silting up reservoirs and reducing their storage capacity.

Transboundary water management presents additional complications. The Nile Basin is shared by 11 countries with competing interests, while Lake Victoria spans Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. Disputes over water allocation occasionally strain diplomatic relations, particularly regarding large infrastructure project like Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam.

Innovative Solutions and Adaptation Strategies

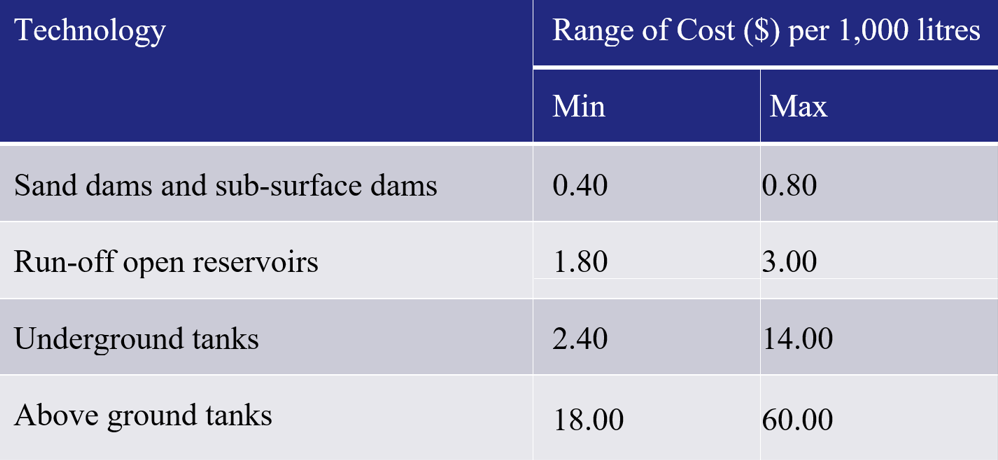

Promising water harvesting technologies are gaining traction across East Africa. Kenya’s sand dams – barriers that trap sand water in seasonal riverbeds – provide reliable water sources during dry months at a relatively low cost. These structures increase groundwater recharge while reducing evaporation losses.

Table 1: The relative cost, per 1,000 litres, for different water technologies. Source

The agricultural innovation extends to drip irrigation systems, which deliver water directly to plant roots, which can achieve efficiency rates of up to 90% compared to 40-50% for conventional methods.

Water recycling presents another frontier as demonstrated in Uganda’s capital, Kampala which is using wastewater treatment facilities to generate biogas energy. Along with powering its own generators, this has also created economic incentives for better water management.

All this ties into early warning systems for hydrological extremes that have been improving substantially as seen with the IGAD’s Climate Predication and Application Centre providing seasonal forecasts and drought warning with increasing accuracy that allow communities and governments to prepare for water-related disasters.

Kenya’s 2016 Water Act established a rights-based approach to water access and created frameworks for sustainable resource management with Tanzania having implemented water pricing reforms that better reflect resource value while protecting access for vulnerable populations

Economic and Social Implications

The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction states that between 2020-2022, more than 30 million people across the East African region have experienced drought-related food insecurity. Nature also estimates that there has been about $70 billion in losses over the past 50 years over the entire content due to droughts. Health impacts also compound this cost, with waterborne diseases costing Sub-Saharan economies an estimated $8.4 billion each year in GDP and health budgets.

Women and girls are also socially implicated by water access disparities. They bear the primary responsibility for water collection in most communities, with time spent gathering water reducing educational and economic opportunities.

Perhaps the most concerning is the relationship between water stress and conflict with a 27% increase in disputes over water resources within the Sub-Saharan region, particularly in areas with drinking wells and grazing areas.

Conclusion: The Path Forward

East Africa’s water crisis demands urgent, coordinated action across multiple fronts. Integrated water resource management approaches that consider the full hydrological cycle and diverse needs hold particular promise such as with Kenya’s Water Resources Authority using catchment-based planning that balances environmental sustainability with human needs.

The African Development Bank’s committing over $8 billion for water and sanitation projects across Africa demonstrate the importance of international cooperation in managing shared water resources and mobilising necessary funding with a focus on resilient infrastructure and governance improvements.

Ultimately, addressing East Africa’s water challenges requires the recognition of water as both a fundamental right and a limited resource requiring careful stewardship. With thoughtful management and sufficient investment, the region can transform current scarcity challenges into opportunities for more sustainable, equitable development. The path forward demands not just technical solutions, but genuine political commitment to ensuring water security for current and future generations in this vulnerable yet vital region.