Meeting East Africa’s Resource Needs: The Relationship Between Self-Reliant Infrastructure and Wide-Scale Grid Operations

Of East Africa’s energy-related challenges, widespread lack of access to electricity is a strong contender for most pressing. While notable progress has been made, it only takes the perusal of IEA data, or better yet, research done by JEPA Africa to get an accurate picture of the dire situation. Lack of access to electricity in East Africa stems from the tug of war between low capacity and insufficient infrastructure connecting homes to the (already strained) grid, and is intensified by an insufficient budget to address these challenges.

Aside from poor access to electricity, 226 million people in East and Southern Africa lacked access to basic water services in 2022. With frequent bouts of droughts and flooding wreaking havoc, there has been intense damage to existing water infrastructure, exacerbating the need for safe and reliable drinking water sources. Inadequate access to water services compounds the prevalence of water borne diseases, which is as high as 88% in Uganda.

While erratic weather affects the reliability of natural resources, it remains that East Africa has an abundance of fresh water and renewable energy resources that can be harnessed by individuals, without the introduction of advanced and expensive national-scale energy and water infrastructure. Utilising these resources on a household scale could be the way forward.

Current State of National Utility Providers

East Africa is overwhelmingly powered by renewables. Ethiopia leads the pack with a 97% hydro powered grid, while Uganda, Rwanda, and Kenya follow similar trends. Despite this, much of East Africa’s ‘clean’ energy resources remain underutilised. In Somalia, electrification rates sit at 17%, despite the nation having the largest offshore wind potential on the continent.

Many national utility providers struggle to achieve capacities that would support existing demand, let alone projected demand required to hit target economic growth. Rwanda, for example, aimed to quadruple household electricity access within a year in 2017. However, despite encouraging efforts, capacity has only been increased from 210.9 MW to 332.6 MW in the years since. Low capacity has also been the cause of frequent outages and load shedding across the region.

The lack of capacity is exacerbated by insufficient funding brought about by low electrification rates. Utility companies often have insufficient clients to make substantial revenue that can be reinvested into maintenance and improvements. For example, faulty meters cost Kenya’s KPLC millions of dollars annually. Many tactics have been attempted to remedy tight budgets. In Rwanda, electricity tariffs sit at $0.22 per kWh compared to its neighbours’ $0.12 per kWh average, while Uganda’s UEDCL recently borrowed over $1 billion to facilitate its transition to full state-control.

The situation with water access mirrors – if not outdoes – the concerning realities of electricity access, and has worsened in recent years, partly due to flooding and droughts, and partly due to political instability. In Ethiopia the number of people lacking water, hygiene and sanitation services rose from an already alarming 7.3 million in 2020, to a staggering 20.5 million in 2023. In South Sudan, 41% of the population lacks reliable access to clean water, as does about half of Somalia’s population.

While climate and weather can affect water availability and damage essential infrastructure, the poor maintenance of wells and boreholes is the primary cause of the region’s rural water insecurity. In urban areas like Nairobi’s Mathare slum, where only 20% of residents have access to piped water, and 40% of pit latrines are within 15 metres of wells or other communal water sources, poor water access is caused by infrequent and insufficient updates to infrastructure.

Self-Reliant Household Infrastructure

Self-reliant – also known as autarky – infrastructure denotes additions to homes that facilitate the harnessing of resources from the immediate environment to meet household needs. A common example of autarky infrastructure is solar panels, widely used within East Africa where large populations live ‘off the grid’. The prevalence of solar panels is due to the region’s overwhelmingly sunny weather and high number of daylight hours throughout the year. Already, over 1.8 million Kenyans use solar home systems.

Biofuels, already the largest energy source in the region, avail even more self-sufficiency options for East African households. Food and animal waste can be collected and converted into fuels that can provide heating and/or fuel for cooking.

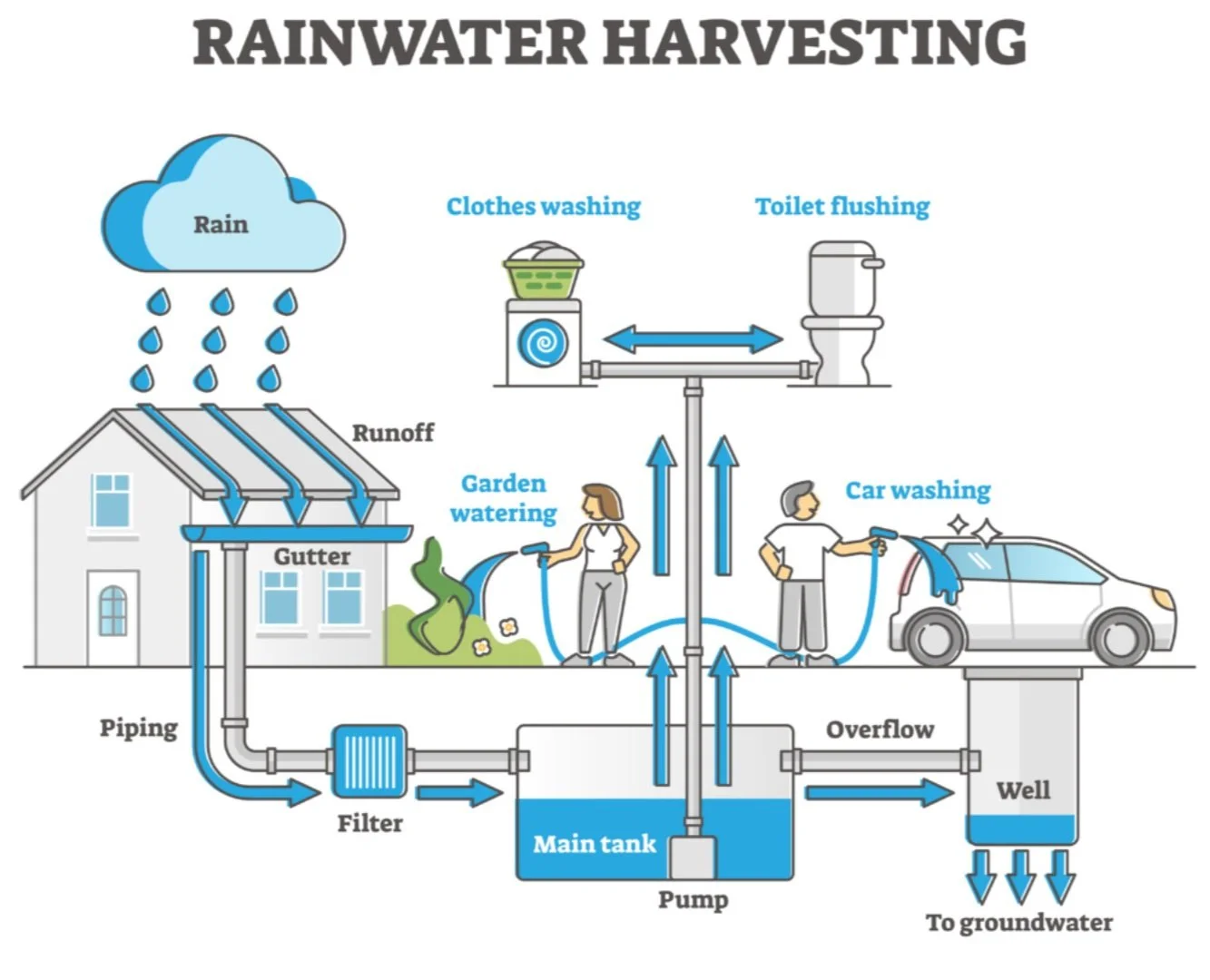

In terms of water autarky, rainwater capture is the simplest and most widely practiced method. Already, 3 in 4 Ugandan households harvest rainwater, and this trend is consistent across the East Africa. It can involve anything from bucket collection during rainy periods, to specially designed roofs directing rainwater into designated collection zones. The accumulated water can then be used for various cleaning tasks.

Figure 1: Rooftop rainwater harvesting schematic. Source

In-house water treatment is an advanced emerging technology that would allow households to independently make water safe for consumption. This would typically involve outfitting a home with filtration systems around water collection points.

Autarky infrastructure would swiftly provide millions of East Africans with assured access to water services and electricity and independence from the grid that would inevitably save them large amounts of money.

Electricity autarky infrastructure in particular could beget a symbiosis between providers and consumers, allowing consumers to generate enough energy to sell a surplus back to the grid. This would mean that ordinary civilians would not only be self-sufficient but would also be able to earn credits on their energy generation. Electricity providers would in turn benefit from the subsequent increases in their electricity capacity, with households generating power on their behalf.

The introduction of water autarky infrastructure would allow more households to grow and tend to plants around their homes. This would be especially beneficial in slums which, albeit urban, are often not served by national utility providers. Food insecurity in slums is also high, at about 85% in Nairobi’s slums. If water autarky accompanied existing communal garden efforts, it could be instrumental to alleviating food insecurity in slums.

A unique benefit of water autarky infrastructure is that it represents a return to an age-old norm: living in tandem with one’s environment was the convention. For many communities, especially rural and nomadic communities, this remains the case. Solving developmental challenges by leveraging indigenous knowledge and practices – collecting rainwater, using dung and plant waste as fertiliser or fuel, among others – is an easy adjustment that would benefit communities and align with environmentally-conscious community practices.

However, autarky infrastructure comes with disadvantages as well, the largest being that it could reduce revenue for operators. If consumers gain autonomy from the electrical grid or develop the capacity to collect and purify their own water, already unprofitable national utility providers would lose clients and make even less revenue, causing perpetual cascading effects.

Some home installations, like solar panels, windmills, and home filtration systems, might only be affordable to the middle and upper classes. In Uganda, home solar setups can total up to $3,800, which, in a nation whose average income is below $1,400 in its capital city, is far beyond what most ordinary people can afford. Home filtration systems can cost several times more than solar panels and require regular expensive maintenance.

Additionally, as self-reliance renovations aren’t always government-run, a lack of centralised regulation could cause inconsistencies in infrastructure quality and result in safety concerns like contamination, damage to appliances, plumbing issues and increased utility bills.

Solutions and Future Possibilities

While there are disadvantages to self-reliant infrastructure, the benefits prevail. Most aspects of autarky are already undertaken by those living ‘under the grid’. Streamlining these practices would allow more people to independently and safely secure access to water and electricity.

Concerted government participation would be necessary to promote and fund the wide-scale implementation of autarky infrastructure. Regulatory bodies would need to be established to assure quality, while subsidies and grants, like those provided by Tanzania’s Rural Energy Agency, would permit more low-income households, which are more likely to lack access to water and electricity to begin with, to access upgrades. Financial support from companies like Bboxx in Rwanda and M-Kopa in Kenya would also broaden access to self-reliant infrastructure.

Furthermore, increasing the number of industrial customers could fill the gap created by losing residential customers. For electricity providers particularly, the growing prevalence of electric vehicles will undoubtedly increase revenue. The possibility of widespread charging stations – analogous to existing petrol stations – would create an assured revenue stream that could compensate for reduced consumer spending.

Autarky infrastructure could be implemented on a wide scale as a short-term solution to pressing energy and water problems. Long-term projects could maintain a focus on improving national utility services. The construction of other basic infrastructure – like boreholes, and proper toilets in slums – is of equal importance, and no amount of autarky infrastructure could negate the need for such structural improvements. Innovative approaches to getting more households connected to utility services, like aerial piped water systems in Kibera, Nairobi, should also be explored. Ultimately, a multi-pronged approach to energy and water infrastructure will be the key to ensuring universal access to water and electricity across East Africa.