Carbonds: Demystifying Carbon Credit Markets

A decade ago, anthropogenic climate change was a highly controversial topic, with many governments and corporations – particularly in the oil and gas sector – actively denying its existence or downplaying its significance. As scientific consensus solidified, and extreme weather events intensified, outright denial declined, and global initiatives became increasingly focused on climate solutions. One such example is the carbon credit market which entails the commercialisation of carbon emission reduction or prevention, to incentivise countries and companies to contribute to climate change mitigation. Carbon pricing is theoretically a win-win solution for major polluters – who can compensate for carbon emissions beyond their means – who fund carbon offset initiatives for those that otherwise couldn’t afford to.

This is an appealing solution for East African countries which, despite their limited role in global pollution, are unequally yoked with the consequences of increased floods and droughts. Most countries in the region are categorised as Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and caught between a rock and a hard place when it comes to choosing between development – which is closely correlated with pollution – and securing a safer future. Funding through carbon credit markets would ideally solve this dilemma. However, carbon trading is heavily scrutinised for falling short in carbon sequestration expectations, and potentially exacerbating economic inequalities, raising social concerns and posing long-term environmental challenges. This article examines carbon credits as a potential solution for East Africa, analysing both their benefits and shortcomings in addition to providing solutions to enhance their effectiveness.

Understanding the Carbon Market

A carbon credit/offset is a tradable unit that represents 1 ton of carbon dioxide theoretically removed or prevented from reaching the atmosphere, otherwise known as carbon offsetting. There are three ways to carbon offset, either through the reduction of emissions, for example, replacing coal cookstoves with renewable energy alternatives; the removal of emissions, for example, planting trees or using carbon-capture technologies; or completely avoiding carbon emissions, which is largely forest conservation. The carbon pricing market, which is forecasted to reach $136.32 billion in 2025, is split between the compliance market – where governments and companies purchase carbon credits to cut emissions below a legally dictated threshold – and the voluntary market – where entities opt to purchase carbon offsets.

Figure 1: Life cycle of a carbon credit. Source

The terms carbon credit and carbon offset are often used interchangeably and decisions to purchase them are governed by two main principles: permanence and additionality. Permanence begs the question ‘is it going to last?’, seeing as climate change impacts more than a lifespan. For example, when considering investments in the protection of a forest through carbon offsets offered by a particular company, it would be wise to consider the fact that once the company no longer exists, the forest would no longer be ‘protected’. On the other hand, additionality considers questions like ‘how do you know the forest wasn’t going to be cut down if you didn’t pay for it?’ to evaluate whether carbon credits add value to mitigation efforts.

East African Context

East African nations have an average per capita carbon footprint of less than one tonne of carbon dioxide annually, with Ethiopia, 0.2, Kenya, 0.6, and Uganda, 0.2 highlighting the stark contrast to developed nations like the United States, where the average per capita emission is 17 tonnes. Generally, more developed countries have higher carbon footprints, indicating a historical correlation between development and carbon emissions because of industrialisation and rapid growth. While many African nations have discovered oil and opportunities in energy markets, the entry barrier to economic prosperity has risen beyond investment in industrialisation. Developed nations experienced multiple industrial revolutions while few laws were exercised to consider the future ramifications, in contrast the pressure to consider sustainability hangs heavy on African nations.

Figure 2: Correlation Between Development and Carbon Emissions. Source.

Economic Impact

The Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are climate action plans submitted by countries under the Paris Agreement to reduce emissions and adapt to climate change. According to the African Development Bank (AfDB), East Africa would need to cover a $60 billion financing gap annually to meet its NDCs. This would require massive investment in sustainable infrastructure though the region is already experiencing critical debt burdens mainly due to high infrastructure spending.

Hence, carbon markets could be a solution to bridging climate funding gaps without garnering even more debt and undermining economic development. Though all of Africa partakes in only 2% of the global carbon credit market, that is predicted to increase given the continent’s rich potential for carbon sequestration; particularly in forestry.

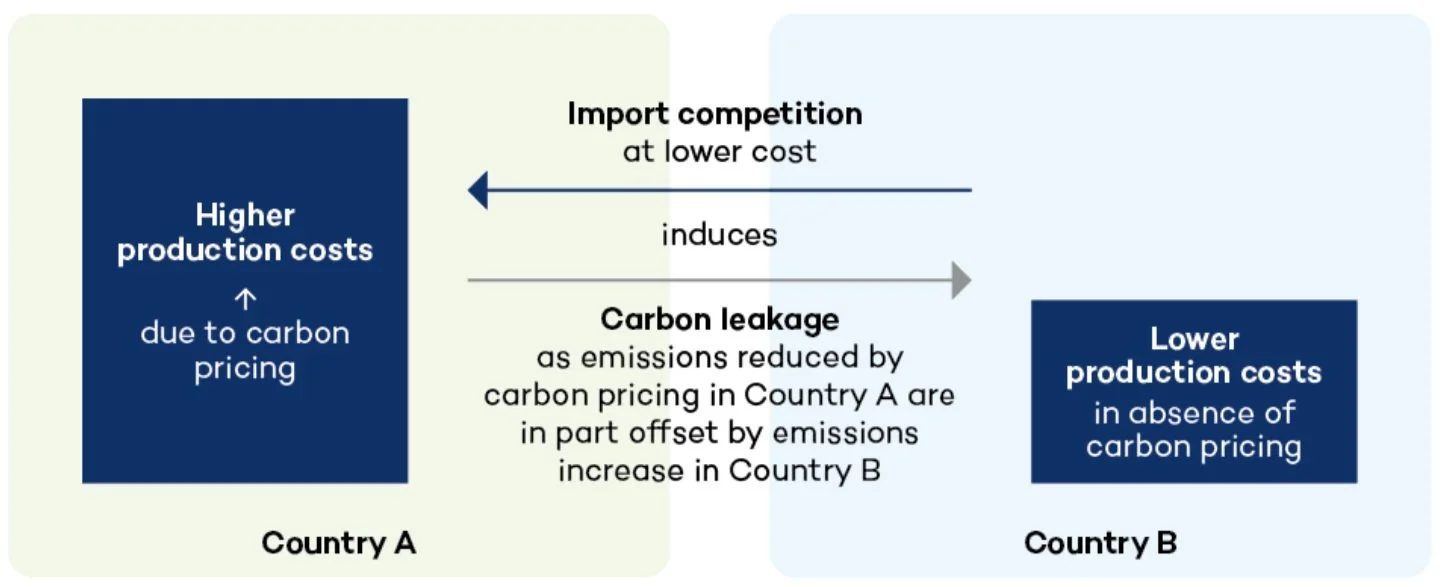

Conversely, the economic downsides of carbon credit markets may discourage East African countries from participating, particularly due to market inefficiencies, over-crediting, and the potential for increased inequality. The lack of multilateral carbon credit pricing mechanisms leads to disparities in pricing and increases the risk of carbon leakage which East African countries are more vulnerable to. Additionally, a significant portion of the carbon market has been found to overestimate emissions savings by issuing more credits than actual emissions reductions achieved, leading to market volatility and unreliability.

To reap the benefits of multilateral carbon credit pricing mechanisms, East African countries should unify regional carbon markets, similar to the European Union Emissions Trading System. By uniting their markets, they could strengthen their negotiating power in global discussions and secure better terms from carbon credit projects. Especially because majority of the world’s voluntary carbon market projects are located in Africa.

Figure 3: Carbon Leakage Explained. Source.

Environmental Impact

East African countries are largely represented in the top 30% nations that are most vulnerable to climate change. The impacts of severe droughts and floods have been exemplified in the region in increasing measure over the last couple of years. Given that over 70% of the industries in the East African Community are agro-based, the threat to biodiversity, particularly to plant and animal food sources is a critical concern for the region.

Carbon credit projects present a potential solution by buffering current and long-term environmental consequences of extreme weather events. Especially because research suggests that forest carbon offsets are the preferred choice for carbon offset projects, these include reforestation, forest conservation, and improved forest management. Forests are an essential aspect of the earth’s water cycle; helping mitigate the frequency and impact of floods and droughts by acting as a sink for excess rainfall and a source for water during dryer periods.

However, the effectiveness of the benefits of forest carbon offsets are dependent on the extent of plant diversity retained or gained. Most reforestation projects involve the planting of one kind of fast-growing tree to quickly induce the benefits of carbon sequestration at the expense of forest resilience. This raises concerns about the permanence of such projects, as monocultures are less likely to withstand extreme weather events when compared to mixed forests, which are often considered too costly to establish and take longer to yield tangible benefits. Therefore, when engaging in carbon offset projects, it is crucial to evaluate their long-term environmental impacts to truly assess their effectiveness.

Social Impact

Carbon offset projects are expected to improve the economic, environmental and therefore social livelihoods in areas of operation. The cumulative effects of an influx of funding for development and reduced climate change impact would ultimately lead to longer, healthier and enhanced lifestyles. For example, carbon credit initiatives could fund renewable energy projects, ideally expanding electricity access to more than half of East Africa’s population, which currently lacks reliable power infrastructure.

However, reports of the social drawbacks of carbon credit schemes appear to be more substantial than those supporting their social benefits. Multiple human rights violations have been triggered by carbon offsetting projects, with cases of indigenous communities forcibly evicted for nature reserves and harassment and abuse of employees. The main reasons being a lack of strong safeguards for human rights in addition to the threat of the power imbalance between governments/companies that determine carbon credit terms, and the often disadvantaged less-developed regions and communities that lack the expertise to negotiate at equal footing.

To address these challenges, nations and communities affected by carbon offset projects must be well-informed and equipped with the necessary skills to negotiate fair terms, ensuring these initiatives deliver genuine and sustainable benefits. For instance, Verst Carbon is a Kenyan company that functions as a bridge between carbon credit project owners and affected communities by offering contextualised training and advice to level the playing field.

Conclusion

In conclusion, carbon credit markets present a promising opportunity for East African countries that are currently juggling the delicate balance between development and climate change action. Carbon credit trading offers economic benefits by attracting funding for sustainable projects without depleting resources for industrial development. However, the market is yet to be reliably efficient, which could then undermine the long-term success of these initiatives. Moreover, the social and environmental concerns associated with carbon credit usage highlight the need for stronger safeguards and fairer negotiations to tackle to potential for human rights violations. To harness the full potential of carbon credit markets, it East African countries should unite their regional markets, strengthen governance structures, and ensure that local communities are equipped to negotiate fair terms. In doing so, the region can better ensure the carbon credit projects deliver meaningful, sustainable benefits for both people and the planet.