Reinforcing the Path to Climate Sustainability: Addis Ababa Charts a Bold Course at the Second Africa Climate Summit

The Second Africa Climate Summit (ACS2), which convened in Addis Ababa from 8–10 September 2025, marked a turning point for Africa’s climate diplomacy. The adoption of the Addis Ababa Declaration on Climate Change and Call for Action, alongside the creation of the Africa Climate Innovation Compact (ACIC) and the African Climate Facility (ACF), framed Africa not only as a continent vulnerable to climate shocks but as a pivotal player in the global climate arena. The inaugural Africa Climate Summit, held in Nairobi in 2023, had already laid a foundation by calling for reforms in international climate finance and issuing the Nairobi Declaration. However, Addis Ababa’s ACS2 went a step further by introducing actionable instruments and quantifiable targets, seeking to transform Africa from a petitioning bloc into a solution-driven powerhouse.

Having unfolded amidst increasing climate shocks and global financing stalemates, this year’s summit illustrated Africa’s vision to reframe itself as a solution hub as leaders, civil society, private-sector stakeholders, and international allies, including representatives from the African Union (AU) and United Nations (UN), converged to set a transformative agenda. Its objective was not only to signal political unity, but also to forge tangible frameworks and mechanisms encompassing financial, technological, and institutional pathways that can shift Africa’s climate engagement from rhetoric to scalable impact.

Central to the summit was a rallying cry for grant-based, dependable climate finance, continental cooperation, and industrialisation pathways that build resilience while leveraging Africa’s rich natural resources. This analysis explores the substantive outcomes of ACS2, covering thematic developments from financing and adaptation to geopolitics and private-sector commitments, set against the backdrop of the global climate governance landscape and Africa’s preparatory roadmap toward the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP30) in Belém, Brazil.

The Addis Ababa Declaration

A significant outcome of the summit was the Addis Ababa Declaration on Climate Change and Call for Action, a political pact with both moral weight and operational goals. The declaration underscored Africa’s disproportionate exposure to climate shocks relative to its minimal historical emissions and demanded equity in global finance flows. Consequently, four immediate pillars of action were outlined. The first was adaptation-first development that placed resilience at the centre of planning, followed by just energy transition with a strong emphasis on renewables and green industrialisation, which leveraged Africa’s critical minerals and labour was highlighted. Lastly, the need for institutional follow-up mechanisms was included, such as monitoring dashboards and unified positions at multilateral fora

The declaration’s innovation lies in its implementation roadmap. It calls for biennial reviews of commitments, ensuring progress reports are tabled at the AU summits. This mechanism aims to avoid the ‘declaration fatigue’ that has plagued similar initiatives. By consolidating a continental voice, Africa also gains stronger negotiating power on the road to COP30. However, turning words into action would require the fuel of finance.

Finance Pathway

A standout moment from the summit was the unveiling of two flagship financial vehicles, the first being the Africa Climate Innovation Compact (ACIC), an innovation-to-scale platform intended to support 1,000 African climate solutions by 2030 across energy, agriculture, water, and resilience sectors. The compact emphasises grassroots innovation, aiming to ensure that local entrepreneurs are not locked out of global finance flows. The second was the African Climate Facility (ACF), a continent-wide financing vehicle, designed to channel concessional capital and grants, lowering risk profiles, and crowding in private investment. It is to be administered with oversight from the African Development Bank and the AU, ensuring continental ownership.

Together, these institutions are tasked with mobilising $50 billion annually in catalytic finance, a figure widely referenced as the scale necessary to transform Africa’s climate landscape.

Regional banks and commercial lenders also signalled parallel commitments estimated between $79–100 billion for renewable energy and industrial projects. However, the challenge lies in translating these figures from pledges into disbursed capital. Civil society groups urged independent verification of these pledges, citing previous experiences where headline figures masked recycled commitments.

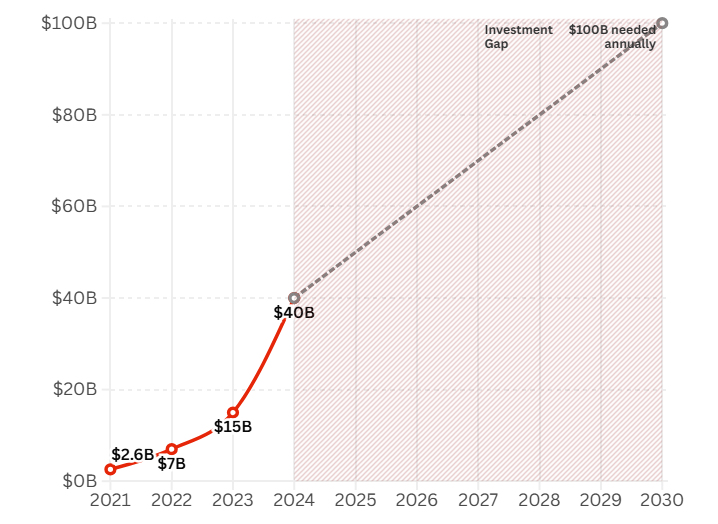

Figure 2: Africa’s Renewable Energy Investment Trend, 2021-2024. Source

According to the UN estimates, Africa will require $2.8 trillion in climate investments by 2030 to stay on track with the Paris Agreement. Yet, the continent currently attracts just 2–3% of global clean energy investment. In this light, the Addis framework thus represents only a fraction of the true financing need, but it remains a significant step in mobilising political momentum and drawing attention to Africa’s financing gap.

Adaptation, Loss & Damage

A notable tonal shift at ACS2 was the elevation of adaptation, loss, and damage. African leaders reiterated that adaptation is not optional but a development imperative. Key demands included predictable, grant-based flows that avoid new debt traps, operationalisation of the Loss and Damage Fund, with direct access for vulnerable communities, as well as integration of resilience into national development plans, rather than impromptu project-based interventions.

The UNDP highlighted the urgency of this approach, stressing that Africa simply cannot afford incremental adaptation measures given accelerating climate risks.

Several countries showcased national adaptation success stories. Rwanda presented its pioneering Green Fund (FONERWA), which channels climate finance directly to communities. Senegal highlighted its coastal adaptation programmes that combine hard infrastructure with community-led mangrove restoration. These case studies reinforced the argument that African governments are not waiting passively for external support but are innovating within constrained fiscal spaces. That focus on resilience naturally flowed into debates on energy and industry, where climate change intersects directly with Africa’s economic outlook.

Energy and Industrialisation

Energy security and industrialisation dominated the summit’s agenda with commitments such as expanding renewable generation capacity through solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal, strengthening cross-border power pools for a more stable regional supply, and promoting green industrialisation, particularly value addition to Africa’s critical minerals such as cobalt, lithium, and rare earths.

Ethiopia used the summit to highlight its flagship Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), symbolising African-led infrastructure development while raising complex Nile basin diplomatic dynamics. The dam adds 5,150 MW of new capacity at a cost of around $5 billion, effectively doubling Ethiopia’s previous installed generation capacity. This leap underscores the transformational potential of single megaprojects in Africa’s energy landscape.

Kenya, meanwhile, announced progress in scaling up geothermal capacity, aiming to become a renewable energy exporter in East Africa. Morocco emphasised its leadership in solar megaprojects such as Noor Ouarzazate, positioning itself as a hub for green hydrogen exports to Europe.

Industrialisation was framed not as extractive exploitation, but as an opportunity to establish resilient, labour-intensive, and locally beneficial industries. Still, the need for robust environmental safeguards was emphasised by community organisations and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to avoid replicating extractive colonial models.

Youth Innovation and Entrepreneurship

While mega projects like GERD symbolised progress on a grand scale, a spotlight was also shone on the creativity of young African leaders, innovators, and entrepreneurs, driving change from the ground up. The newly launched ACIC is set to serve as a continental incubator, supported by challenge funds, accelerators, and market linkages. From off-grid solar startups lighting up rural communities to drought-resilient seed varieties boosting food security. The summit showcased how homegrown solutions are already shaping Africa’s climate future.

Youth voices were particularly prominent. Panels and side-events highlighted start-ups from Ghana, Nigeria, and Kenya that are piloting scalable business models for energy access and climate-smart agriculture. The summit featured a Youth Climate Innovation Marketplace, linking entrepreneurs with investors and technical partners.

This emphasis aligns with demographic realities. With Africa’s median age under 20, empowering youth enterprises is not only a moral imperative but also a strategic economic approach to innovation-driven growth. By 2030, Africa’s workforce is projected to be the largest globally, underscoring the need to integrate climate action with job creation in both the public and private sectors.

Private-Sector and Institutional Commitments

While several financial pledges were made, doubts remain about their practical implementation. The real impact will depend on whether the funds can be structured around concessional and grant-based models, rather than piling more debt onto already strained economies. Success will also rest on setting clear timelines and accountability measures to ensure words turn into action. Furthermore, ensuring resources reach the community-level initiatives that often struggle for support but are effective in building climate resilience on the ground. The World Resources Institute underscored the need for transparent tracking and independent monitoring to avoid ‘pledge fatigue’.

Business leaders argued that a transparent pipeline of bankable projects is required to unlock large-scale private investment. The African Development Bank pledged to expand its project preparation facilities, while multinational corporations signalled interest in renewable energy manufacturing and sustainable agriculture value chains. Commitments from banks and corporations added weight to the proceedings.

Aside from business, Africa’s growing geopolitical leverage was highlighted, reminding the world that climate action is inseparable from diplomacy and regional stability

Geopolitics and Water Diplomacy

Beyond finance and adaptation, ACS2 became a stage for geopolitical signalling where East Africa’s growing geopolitical leverage was highlighted, reminding the world that climate action is inseparable from diplomacy and regional stability. From emphasis on vast critical mineral reserves to renewable energy potential and demographic momentum, Addis Ababa served as both a climate summit and a geopolitical marketplace.

For example, Ethiopia’s celebration of GERD underscored both the potential of African-led megaprojects and the risks of transboundary water disputes. Egypt and Sudan continue to express concerns, highlighting the tension between national sovereignty and regional water security. This moment revealed the dual nature of Africa’s climate and development projects, as instruments of pride and progress, and as potential sources of conflict if diplomacy lags.

Community Perspectives

Civil society organisations played a crucial watchdog role during ACS2. Groups such as Climate Action Network Africa pushed for stronger accountability clauses in the Addis Declaration. Women-led organisations called for gender-sensitive climate finance, while indigenous communities demanded recognition of traditional ecological knowledge in adaptation strategies.

There was also scepticism about the private sector’s role. Activists warned against ‘greenwashing’ and stressed that community-level projects often struggle to secure finance compared to large infrastructure deals. They urged governments to reserve a share of ACIC and ACF funds for local initiatives.

Implications for COP30

By consolidating a unified African voice, ACS2 sets the stage for COP30 in Belém. Africa will arrive with a sharpened agenda: adaptation-first financing, operational loss and damage mechanisms, and a strong case for African-made climate solutions.

If the outcomes are translated into transparent, inclusive, and grant-friendly capital flows, Africa could significantly influence global climate negotiations while simultaneously advancing its development priorities. Moreover, the credibility of Africa’s position will depend on whether progress between ACS2 and COP30 demonstrates genuine implementation, not merely declarations.

Conclusion

The Addis Ababa summit was more than just another climate gathering; it was a clear statement of intent. Africa is repositioning itself from the edge of climate diplomacy to the centre, as both a testing ground and a marketplace for solutions. The Addis Ababa Declaration, ACIC, and ACF are ambitious steps in the right direction. Their success and impact will hinge on how well they are governed, how inclusive they become, and the follow-through of financial commitment.