Safeguarding Tomorrow: A Call for Comprehensive Cybersecurity in the Growing Field of Education Technology

In the age of Artificial Intelligence (AI), the conversation on cybersecurity has broadened from protecting just data to protecting the very meaning of humanity from cyber-attacks. This concern is evident in the existence of networks such as World, which serve as a means to prove human identities in digital spaces to protect people from threats such as deepfakes. World is powered by a science fiction looking orb that takes an image of your iris and face, converts them into a unique code that undergoes processing to become a World ID. Kenya was the first African country to undergo orb registrations in exchange for up to $49 per person. Thousands queued up to register for up to three days, however, the Kenyan government expressed concerns for the safety of its citizens before suspending registrations in 2023. In 2024, Kenya’s legal investigations on World dropped with indications that registrations will resume.

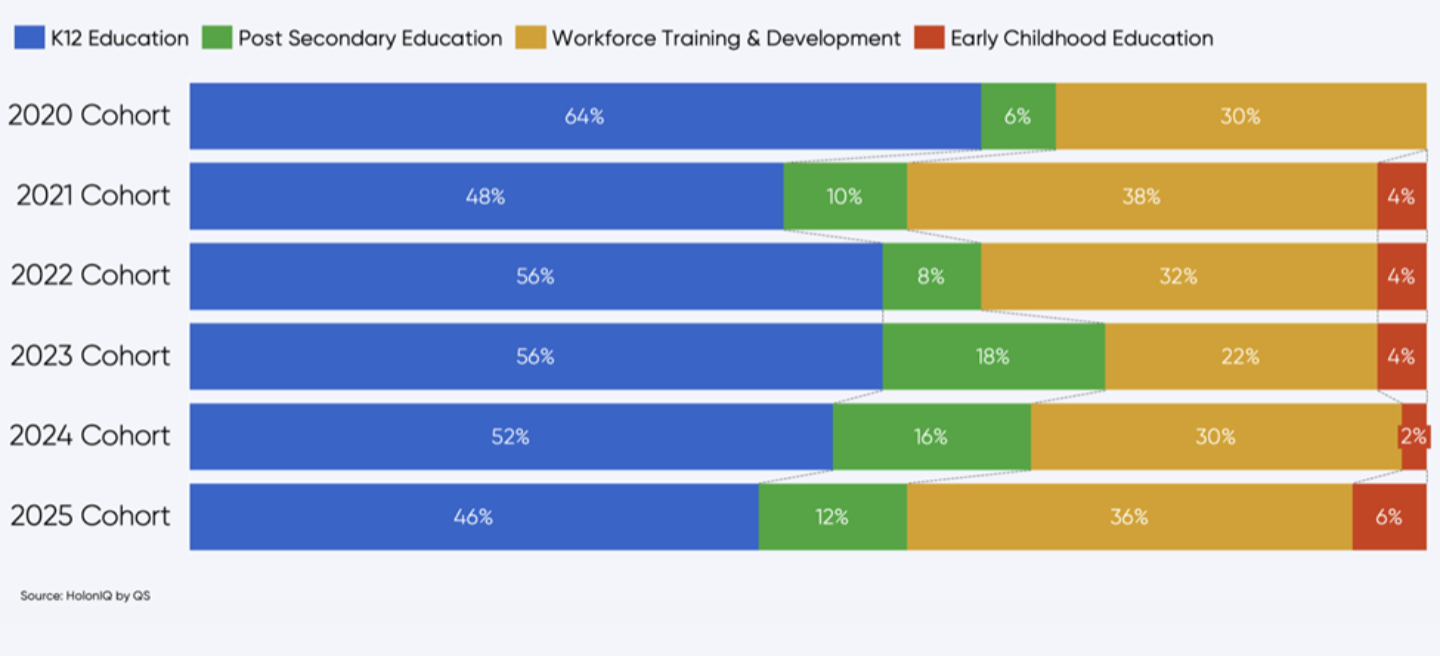

Against this backdrop, it is increasingly vital that education systems equip young people with the skills and awareness needed to navigate an AI-driven world. Continental data shows that Africa’s EdTech spending is expected to rise from 1% to between 6 to 10% by 2030, reaching $57 billion, signalling long-term dependence on digital systems for teaching and administrative operations. This shift makes the protection of children’s data a core educational priority because digital platforms collect information ranging from login details and behavioural analytics to biometric markers depending on the tool used. Young children, whose cognitive development and digital literacy are still emerging, remain especially vulnerable to risks such as data misuse, profiling, cyberbullying, and commercial exploitation. As East Africa becomes more deeply embedded in digital education ecosystems, safeguarding student privacy is foundational to equitable, ethical, and safe learning. The following sections outline the contextual challenges, major risks, and policy-aligned solutions for governments, schools, ed-tech companies, and families across the region.

Figure 1. Africa’s ed-tech sector distributions from 2020 to 2025. Source.

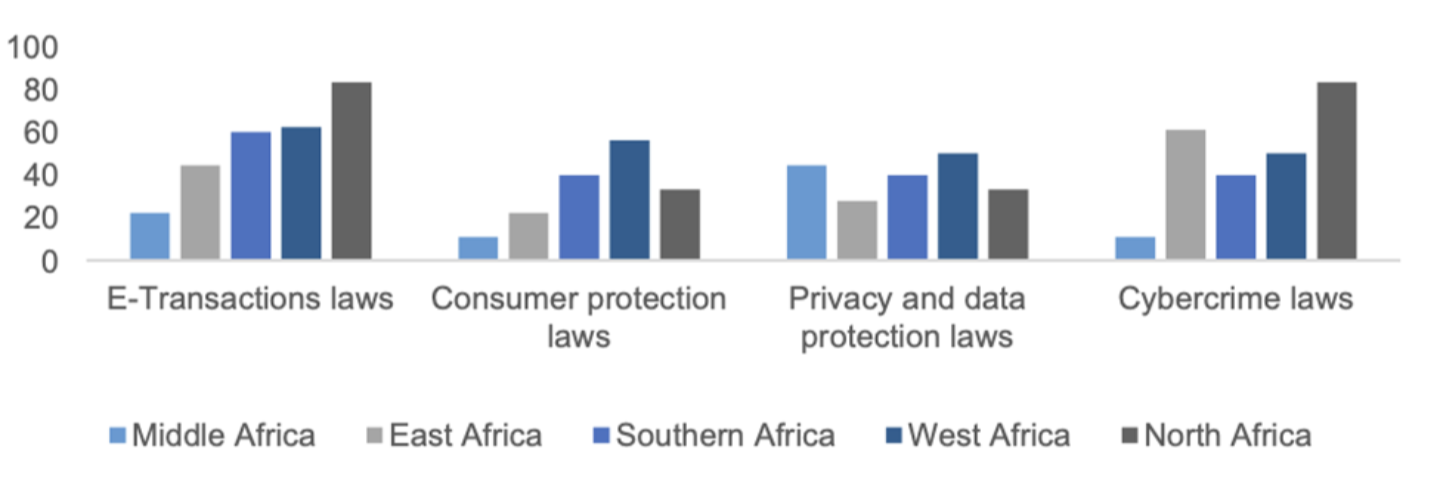

One of the biggest problems right now is that digital ecosystems are growing faster than the policies and systems designed to regulate them, creating structural vulnerabilities in data protection. Ed-tech platforms range from television shows and YouTube channels such as Tanzania’s Ubongo Kids; to administration apps like Kenya’s Zeraki app; to AI powered gamified education tools similar to Ethiopia’s Askuala app. A study on AI-enable ed-tech applications from across Africa show that 50% of these platforms lack publicly accessible privacy policies, even after user registration, and only 18% mention children’s rights or parental consent procedures. In 2017, East Africa ranked lowest when it came to privacy and data protection laws in comparison to the rest of the continent. This mismatch between platform usage and regulatory readiness exposes especially vulnerable students to data exploitation and surveillance without their knowledge. The region therefore faces a critical need to align expansion of ed-tech tools with regulatory frameworks, localised protections, and accessible, child-friendly data agreements.

Figure 2. Percentage share of economies with relevant e-commerce legislation in Africa in 2017. Source.

These findings highlight the urgent need for governments to enforce data protection laws that hold organisations accountable. A paper from the Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Technology Law (CIPIT) at Strathmore University advised that legislation should mandate that every ed-tech platform display clear privacy policies outlining: the platform owner, the legal basis for collecting information, the types of data collected, access by third parties, security safeguards, user rights, and data retention timelines. All of which should be understood by relevant stakeholders including children by providing simplified privacy policies they can understand. In East Africa, where reliance on foreign platforms is high, governments must set standards to ensure that imported tools protect children’s data to the same degree required locally and encourage private sector participation to ensure long-term sustainability. Moreover, they should regularly audit ed-tech companies and ensure mandatory teacher training on data privacy.

Additionally, strengthening student privacy in East Africa also requires empowering parents, guardians, and local communities with accessible, culturally relevant tools. It has been found that the financial burden of devices and connectivity often falls on households, limiting equitable adoption of digital learning. Unfortunately, many parents lack the digital literacy to understand platform risks or navigate privacy settings. To address this, privacy agreements and cybersecurity resources must be translated into major regional languages and simplified to meet different levels of digital literacy. Educational ministries, NGOs, and schools can collaborate to distribute printed guides, run parent workshops to deliver basic cybersecurity training, and offer affordable device-protection solutions. Such as contextualised adaptations of the United Kingdom’s “10 Steps to Cyber Security”, which offer guidance on avoiding threats, safely managing logins, and reducing home-based vulnerabilities. Additionally, governments should allocate targeted budgets or subsidies to low-income families to ensure that privacy does not become a privilege accessible only to the wealthy.

As the world undergoes rapid digital transformation, privacy protection and threat awareness must become educational priorities. The dangers of inadequate cybersecurity education were starkly illustrated when thousands of Kenyan citizens lined up to register their biometric data with Worldcoin's Orb. Many were motivated purely by financial incentives, with one participant admitting, "I liked Worldcoin because of the money. I'm not worried about the data being taken. As long as the money comes." This statement reveals a dangerous gap in public understanding of data rights and digital exploitation. Without awareness of cybersecurity risks and their long-term consequences, individuals, particularly young people, become vulnerable to exploitation. Governments must implement preventative measures that outpace technological advancement through comprehensive strategies: school systems must be equipped with robust data management processes; ed-tech organizations must be held accountable for transparent, child-specific privacy policies; and parents must be supported with accessible, multilingual cybersecurity resources. Equally essential is ensuring equitable funding and household support, as financial barriers prevent vulnerable families from accessing safe technologies and digital literacy programs.

Conclusion

Ultimately, safe digital learning environments in East Africa will emerge only when all stakeholders including governments, institutions, companies, and guardians share responsibility for protecting children’s data. By adopting proactive and child-centred privacy measures, the region can harness the benefits of technology while safeguarding the rights and wellbeing of its learners.