Learning to Build Bridges: Prioritising Education Integration to Overcome EAC Tensions and Implementation Gaps

‘Kupotea njia ndio kujua njia’ is Swahili for ‘to get lost is to learn the way’; a proverb that can be used to describe the inception of the European Union (EU). After two World Wars, the founding states pursued post-war reconciliation, beginning with economic cooperation, which was exemplified by the decision to pool coal and steel resources to make war "materially impossible". In contrast, the East African Community (EAC) traces its origins to colonial-era arrangements, notably the 1927 colonial customs union. However, it collapsed in 1977 due to political clashes and was revived in 2000 after a hiatus. Tensions that threatened the union persist today with enduring infighting between member states, thanks to the prioritisation of expansion at the expense of relations.

When collaboration focuses on quick gains, self-interest often undermines trust. Amid ongoing implementation gaps such as non-tariff barriers, infrastructure weaknesses, and slow adoption of agreements, as well as rising political friction, education integration could offer a practical, long-term path forward. By harmonising qualifications, expanding student and staff mobility, and supporting joint programs such as the Inter-University Council for East Africa (IUCEA) and the Common Higher Education Area (CHEA) roadmap, this approach can build shared identities, strengthen institutions, and reduce prejudices that fuel conflict. While not a complete solution, seeing as political and security steps remain essential, ‘soft integration’ successes like the EU’s Bologna Process show it can ease tensions and improve execution by investing in people rather than rigid structures. This article assesses whether prioritising educational integration is a strong solution for the EAC’s challenges, particularly interstate tensions and slow implementation of protocols. It outlines the benefits, limitations and downsides of this method, and finally proposes solutions to address these limitations, drawing on current regional efforts and lessons from other models.

Education for Unity

Education integration promotes cultural and normative exchange through scholarships, academic mobility, and joint programmes, therefore enabling mutual understanding, tolerance, and shared values that could reduce prejudices fuelling conflicts. Peace-oriented curricula and student exchanges build social cohesion and cross-border networks, helping to ease political frictions.

Second, it drives capacity building by harmonising qualifications and training a skilled workforce equipped to fill staffing and legal-reform gaps in regional institutions like the EAC Secretariat. Initiatives such as the East Africa Skills for Transformation and Regional Integration (EASTRIP) project demonstrate this potential because it has exceeded enrolment targets, enhanced TVET quality, and reduced labour-mobility barriers, thereby supporting the EAC Common Market objectives and mitigating disparities that delay implementation.

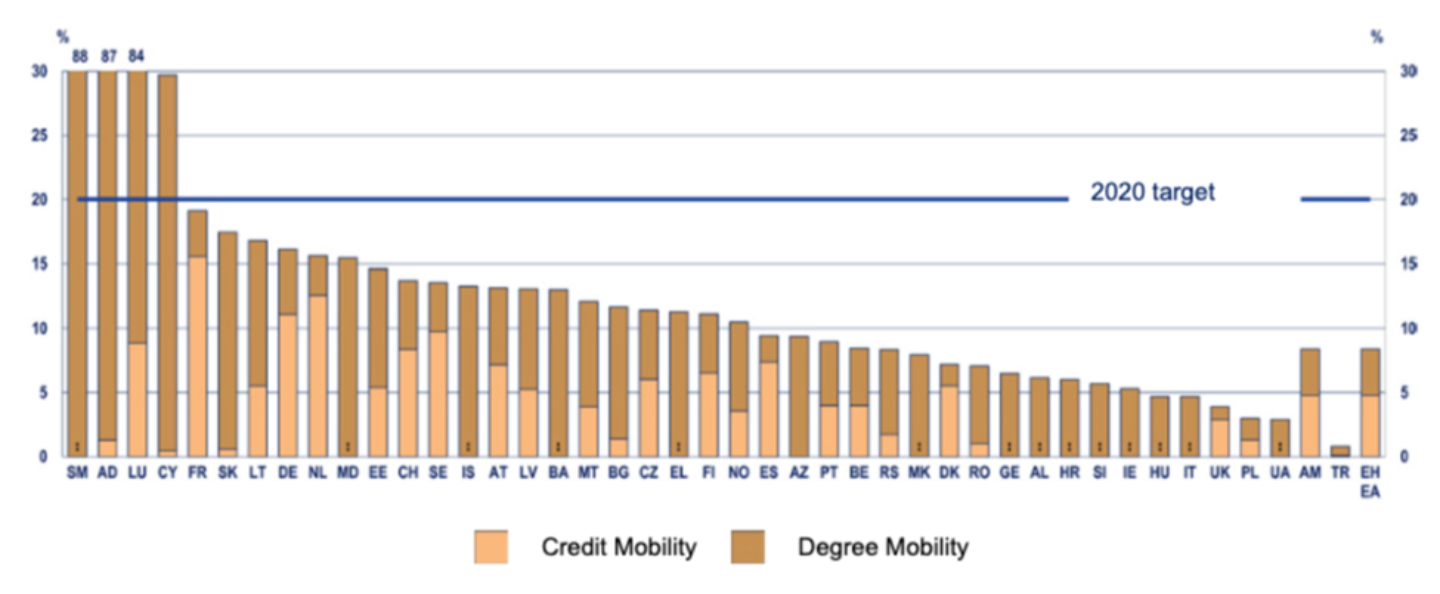

Third, the approach delivers long-term economic and social gains, creating larger, more integrated labour markets, encouraging innovation through knowledge exchange, and lowering conflict risks via sustainable development and peacebuilding. These advantages are evidenced by the EU’s Bologna Process experience, where standardised structures have enabled graduate mobility. The 2024 Bologna Process Implementation Report showed that an average of 15% of university graduates in 2020 studied abroad within the region – either for a short time through a semester exchange – or for a full degree owing to the internationalisation in European higher education by the Bologna Process. This illustrates how harmonisation directly facilitates cross-border movement and the resulting gains in employability, skills, and institutional capacity.

Figure 1: Outward degree and credit mobility percentage rate of graduates by European Union countries of origin, 2020-2021. Source

Challenges

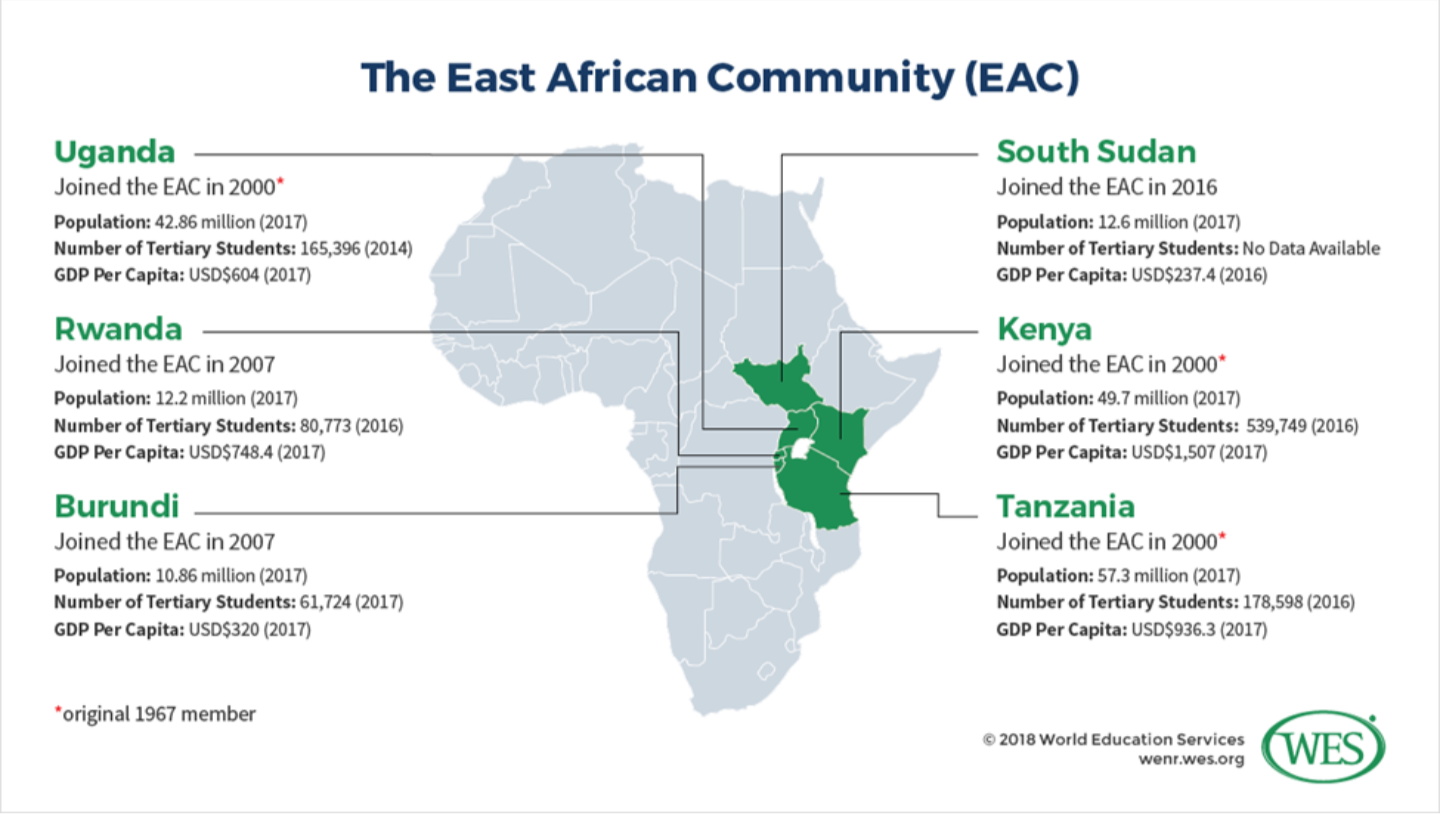

Figure 2. The population, number of tertiary students, and GDP per capita for each ember state in the East African Community as of 2016-2017. Source.

While these benefits position education integration as a powerful long-term strategy, it is not without limitations, including funding constraints, uneven access and power imbalances among member states, and the risk of neglecting immediate crises. Funding shortages hinder effective implementation, as many EAC countries allocate insufficient resources to education. For instance, Sub-Saharan Africa's average education spending is about 4.3% of GDP in 2021, with EAC nations like Kenya at around 5% and Tanzania at around 3%, falling short of the UNESCO-recommended 6% benchmark. This has led to inadequate infrastructure and program scalability an underinvestment that limits harmonisation efforts and exacerbates capacity gaps.

Additionally, uneven access and power dynamics amplify disparities, as wealthier states dominate resources and mobility. In 2017, Kenya had 539,749 tertiary students and $1,507 GDP per capita, compared to Burundi's 61,724 students and $320 per capita, highlighting structural inequalities. 2024 data show persistent gaps, with Kenya's GDP per capita at $2,275 versus Burundi's $344, while tertiary gross enrolment ratios vary from Kenya's ~10% to Burundi's ~6%, potentially widening brain drain and marginalising smaller nations.

Lastly, focusing on long-term education risks overlooking acute political and security crises, such as ongoing conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and South Sudan, which displaced over 7 million in 2025 and caused thousands of deaths, demanding immediate interventions over educational reforms. These limitations underscore the need for complementary strategies to ensure education integration's viability.

Solutions

To address funding shortages, one possible solution would be to establish a dedicated regional education fund, financed through mandatory contributions from EAC member states – (according to capacity–), combined with private-sector partnerships. This model could build on the existing EAC Partnership Fund, channelling resources specifically towards harmonising qualifications, expanding the CHEA, and supporting cross-border mobility programs.

A second possible solution involves scaling up international partnerships and grants, particularly from institutions like the World Bank, which has already invested over $500 million in African higher education through initiatives such as the Centers of Excellence (ACEs) since 2014. By securing multi-year, targeted funding for digital infrastructure, faculty training, and joint research, the EAC could reduce reliance on national budgets, accelerate implementation, and ensure more equitable distribution of resources across member states. These approaches would help bridge the current funding gap and sustain long-term progress in regional education integration.

One potential solution for uneven access and power imbalances could be implementing affirmative action scholarships through the EAC Student Mobility Scheme (EAC-SMS), prioritising applicants from lower-enrollmentenrolment and lower-income countries such as Burundi and South Sudan, to ensure balanced participation in cross-border programs. Another approach could be directing targeted infrastructure investments, via public-private partnerships and regional development funds, toward underrepresented states to upgrade universities, digital connectivity, and TVET facilities. Projects like EASTRIP already demonstrate success in promoting equity by focusing on skills training across borders. Together, these measures may reduce brain drain from weaker economies, prevent dominance by larger states, and foster more inclusive mobility and capacity-building, helping to level the playing field within the EAC’s education integration efforts.

Lastly, to avoid diverting attention from urgent political and security crises, education could be integrated into emergency response frameworks by adopting UNESCO’s Education in Emergencies approach, which delivers mobile learning, teacher training, and psychosocial support to displaced populations while simultaneously advancing CHEA objectives like qualification recognition for refugees. This ensures education contributes to stability rather than competing with humanitarian priorities. Additionally, incorporating conflict resolution, peace education, and intercultural competence into curricula would equip future leaders to address tensions proactively.

Conclusion

Prioritising education integration offers a patient, people-centered solution to persistent tensions and implementation delays within the EAC. Through harmonised qualifications, expanded mobility via the IUCEA and CHEA roadmap, and initiatives like EASTRIP, it could foster cultural understanding, build institutional capacity, and generate long-term economic and social gains, similar to the EU’s success through the Bologna Process which enabled graduate mobility and employability.

However, these benefits must be weighed against real limitations: chronic underfunding, stark disparities in access and economic power, and the danger of sidelining acute crises present in the region. Targeted solutions such as regional education funds with international support, affirmative scholarships and infrastructure equity measures, and hybrid emergency-education frameworks, may be able to mitigate these challenges. Ultimately, sustained investment in education, combined with parallel political and security efforts, can transform setbacks into pathways toward a more cohesive, resilient, and equitable East African Community. By learning from both its own history and global models, the EAC has the potential to turn obstacles into opportunities for genuine unity.