Between Aspiration, Risk, and Strategic Necessity: Assessing East Africa’s Nuclear Energy Potential

East Africa faces chronic power deficits and rapid demand for growth, yet it is considering one of the most capital-intensive energy technologies ever deployed. This paradox defines the region’s nuclear debate. As governments unveil ambitious plans, the central question is whether nuclear power is a realistic medium-term solution or a policy mirage driven by long-term aspiration. Behind the announcements lies a gap between rhetoric and reality, shaped by long timelines, high costs, and institutional capacity limits. While nuclear promises energy security and low-carbon baseload power, its financial, governance, and intergenerational risks are unevenly distributed, raising fundamental questions about who benefits, who bears the costs, and whether nuclear aligns with East Africa’s urgent energy needs.

East Africa’s Power Reality Check

East Africa power market analysis indicates that hydropower is a prominent generational source in East Africa, leveraging the region’s abundant water resources. Major rivers such as the River Nile and reservoirs serve as key assets for large-scale and small-scale hydroelectric projects, providing a cost-effective and renewable energy solution. Kenya is at the forefront in geothermal energy production, leveraging its vast geothermal reserves in the Rift Valley, while Tanzania's energy market share in the region is bolstered by investing largely in hydropower, natural gas, and renewable energy to fuel the increasing demand.

The East African power market size reached 21.7 GW in 2025. Looking forward, IMARC Group estimates the market to reach 29.2 GW by 2034, exhibiting a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 3.33% from 2026 to 2034. The burgeoning electricity demand, driven by significant population growth and urban development, is a key driver of the East African power market. For instance, according to UNICEF, the population of Eastern is projected to surpass 1 billion by 2050 and reach 1.5 billion by the year 2090. Moreover, expanding industries, infrastructure development, and efforts to enhance electrification rates in underserved rural areas have fuelled investments in power generation. Governments in the region are prioritising energy access to support economic development, with significant public and private sector involvement in developing new power projects. The emphasis on sustainable energy solutions is further reinforced by global partnerships and funding aimed at increasing renewable energy adoption and improving grid reliability.

Taken together, these trends indicate a power system under mounting pressure, expanding rapidly in size, yet still constrained by infrastructure limitations. It is within this context that nuclear energy enters policy discourse. The critical question, however, is whether nuclear is being advanced to address a clearly defined technical shortfall in East Africa’s evolving power systems, or whether it reflects a political response to long-term planning credibility challenges.

Mapping the Nuclear Landscape

East African nations are steadily advancing toward nuclear readiness, though each remains at a different stage of development. Uganda’s planned Buyende nuclear plant, with a projected capacity of 2 GW, is expected to deliver its first 1 GW by 2031 in partnership with China’s CNNC.

Kenya has also been preparing for nuclear power for several years, though its timelines have shifted. As of February 2024, its long-delayed programme targeted 4,000 MW by 2035. The Siaya plant is expected to start with 1,000 MW and gradually expand to 20,000 MW by 2040, enhancing energy security and reducing reliance on imports.

At the same time, Rwanda is advancing its nuclear programme, aiming to commission its first plant by 2030 on a 15–50 hectare site, concentrating on small modular reactors (SMRs) and a Centre for Nuclear Science and Technology. The Rwanda Atomic Energy Board (RAEB) has partnered with U.S.-based Nano Nuclear Energy to explore SMR and microreactor deployment.

Tanzania’s engagement with nuclear energy is the most tentative. The National Energy Policy 2015 prioritises natural gas, coal, hydro, and renewables in the generation mix per the Power System Master Plan, mentioning nuclear only briefly as a low-priority option limited by high costs, waste management, and lack of capacity. Policy attention remains focused on expanding natural gas, hydropower, and renewable capacity, leaving nuclear on the periphery of the country’s actual energy transition pathway.

The absence of a harmonised nuclear framework complicates investment, prolongs project approvals, and creates barriers for international nuclear companies. A unified approach to nuclear regulation across the region would not only enhance market accessibility but also streamline compliance processes, foster investor confidence, and accelerate the deployment of nuclear power. Achieving regulatory harmonisation in Africa’s nuclear sector requires coordinated efforts from governments, regional bodies like the African Commission on Nuclear Energy (AFCONE) and the Forum of Nuclear Regulatory Bodies in Africa (FNRBA), and international stakeholders such as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

The Economics of Nuclear Energy in a Low-Income Power Market

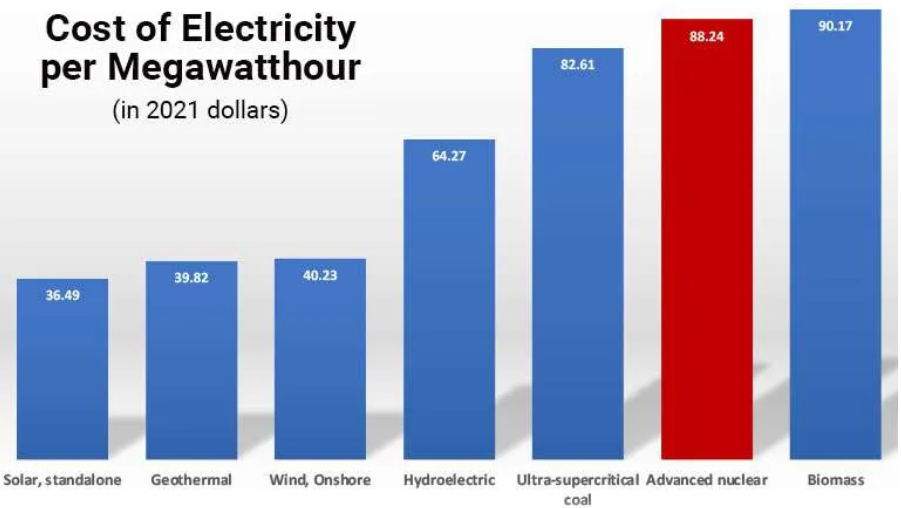

While the cost of renewable energy has decreased significantly, the cost of nuclear energy has, however, increased in the past decades and now generally exceeds the cost of renewables. An analysis of the levelized costs of energy (LCOE) by Lazard Investment Bank indicates that wind and solar energy are five times cheaper than nuclear. The report also concluded that renewables remain less expensive, even when storage and network costs are included, raising questions about the long-term viability of nuclear energy in the region.

Figure 1: A graph indicating the value of production of different types of energy. Source

Significant challenges continue to hinder Africa’s nuclear ambition. East Africa, in particular, requires additional costs and efforts to improve the efficiency of generally underdeveloped nuclear infrastructure and train national staff who will manage, operate, and maintain such projects.

East African countries operate within asymmetrical global energy and finance systems that shape technology choices long before construction begins. Limited domestic capital and the technical complexity of nuclear projects often require turnkey delivery, servicing, and waste agreements with external actors. These conditions can lock host countries into decades-long dependencies on foreign vendors, regulators, and financiers, concentrating influence over critical infrastructure in external hands once nuclear deployment begins. For example, Uganda heavily depends on China and Russia for nuclear projects for financial support.

As the global energy transition accelerates, the debate between nuclear power and renewables remains complex. While nuclear energy offers high-capacity, low-carbon baseload power, it is often hindered by long construction timelines, cost overruns, waste issues and decommissioning challenges.

Potential Alternative: Small Modular Reactors (SMRs)

For Sub-Saharan Africa, where electricity deficits stifle growth, small modular reactors (SMRs) offer a promising solution. Unlike traditional large-scale nuclear plants, which require high upfront costs and extensive water for cooling, SMRs are compact, scalable, and designed for flexibility. With outputs typically ranging from 10 to 300 MW, SMRs can power small towns, mining operations, or urban centres, making them perfect for East Africa’s diverse and often remote landscapes.

However, there are limited but notable examples globally that illustrate the potential of SMRs in practice. Russia’s floating SMR, Akademik Lomonosov, has been supplying electricity and heat to the remote Arctic town of Pevek since 2020, demonstrating deployment in isolated, infrastructure-constrained settings. In China, the ACP100 (Linglong One) SMR is nearing completion as the world’s first land-based commercial SMR, signalling growing technical maturity, though widespread replication remains untested.

This contrast raises a strategic question at the heart of the East African nuclear debate: are SMRs a genuine pathway to enhance energy access and grid reliability, or are they a convenient postponement of the harder decisions about energy strategy, investment readiness, and systemic capacity? SMRs currently sit somewhere between promising innovation and speculative policy hope, offering potential benefits that will only materialise if substantial groundwork, financing commitments, and institutional frameworks are simultaneously developed.

Strategic Takeaways for Policymakers and Investors

Nuclear power sits between long-term strategic potential and near-term risk. In principle, nuclear could act as a future hedge for industrial baseload demand, supporting urbanisation, manufacturing, and decarbonisation once electricity demand, grid capacity, and institutional readiness significantly mature. In the near term, however, nuclear remains a high-risk option. Long development timelines, high capital costs, and regulatory complexity. Nuclear ambitions risk diverting political focus and investment from more immediate and scalable solutions, potentially reinforcing dependency rather than resilience. As such, nuclear may belong to East Africa’s long-term horizon, but not its immediate energy transition pathway. Given the risks, costs, and long timelines associated with nuclear projects, East African countries must carefully consider alternative energy sources. Solar, wind, and medium-sized geothermal power plants offer cheaper and faster alternatives.

Conclusion

Investing in large, expensive nuclear construction projects with uncertain timelines may not be the most prudent path forward for East Africa. A diversified energy mix, prioritising renewable sources and carefully considering the risks and benefits of nuclear power, is crucial for a sustainable and secure energy future. Therefore, the nuclear question ultimately asks whether East Africa is pursuing genuine energy sovereignty grounded in systems it can build, govern, and sustain or symbolic modernity, where the appearance of advanced infrastructure substitutes for delivery.