The Dream Deferred: Why East Africa’s Monetary Union Remains Out of Reach

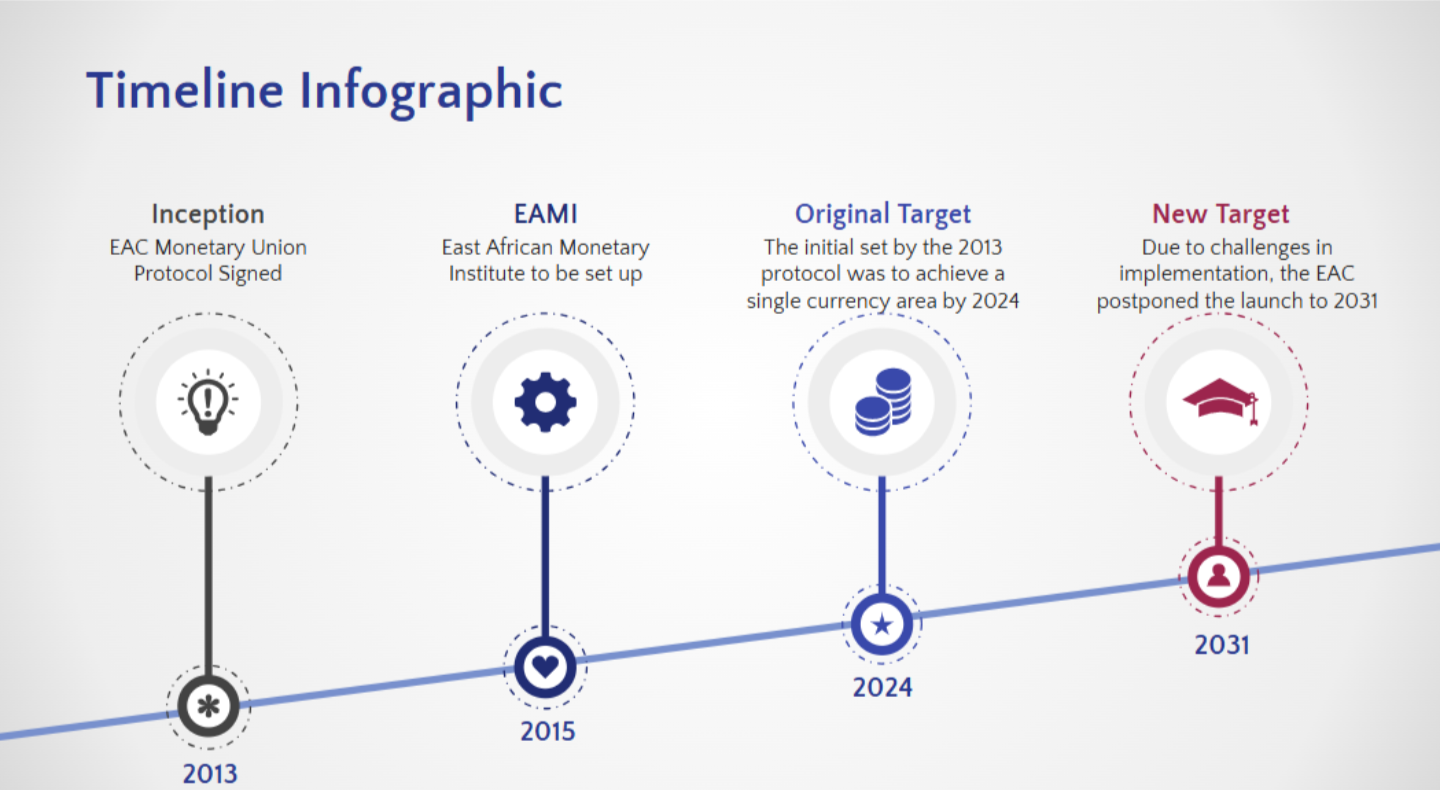

On November 30th, 2013, when the East African Community(EAC) unveiled the Monetary Union Protocol, the mood across the region was almost celebratory. A single currency by 2024 felt like the next chapter of an integration story that had already delivered a customs union, a common market, and unprecedented cross-border movement. Across the different member states, policymakers spoke with the kind of confidence that suggests inevitability; a shared currency was not a question of if, but when.

However, the arrival of 2024 came with neither a new currency nor a regional central bank. The East African Monetary Institute (EAMI) which was put in place as a precursor to the East African Central bank, ideally supposed to issue the single currency, still remains only partly operational. This contrast between ambition and outcome leads us to a difficult question: If East Africa has integrated so much of its political economy, why has the monetary union, arguably its most symbolic project stalled?

The Vision – A Single Currency for a Single Market

As part of the third phase of regional integration, member nations of the EAC signed the Protocol on the Establishment of the East African Monetary Union(EAMU) on the 13th of November 2013 to introduce a common currency by 2024. Indeed, the treaty for the establishment of the EAC, signed by the Heads of State of Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda in November 1999, and entered into force in July 2000, defines four different stages of integration. These consist of a Customs Union, a Common Market, a Monetary Union, and a Political Federation. Burundi and Rwanda acceded to the EAC Treaty in June 2007, while South Sudan gained accession in April 2016.

From the beginning, the idea of a shared currency carried more than a technical appeal, it represented a statement of confidence in East Africa’s collective future. A single currency could help reduce forex-related frictions, specifically eliminating both the transaction costs of exchanging currencies and exchange rate volatility, which are among several costs slowing down intra-EAC trade. It would signal macroeconomic alignment, deepen investor trust, and place East Africa in a stronger position on the global stage.

The roadmap was ambitious but clear: Build the EAMU, transition into a regional central bank, and then launch a currency that moves seamlessly across seven borders.

For a period, this optimism appeared well-founded. The Customs Union had stimulated regional commerce, the Common Market had expanded opportunities for East Africans to study, work, and establish enterprises with reduced regulatory barriers, and regional financial institutions such as Equity Bank Group and KCB Group were extending their operations across borders. In this context, the prospect of a single currency emerged as a logical progression, serving as a potential integrative instrument for a region increasingly interconnected through mobility and trade.

Figure 1: Infographic showing the proposed timeline for the launch of the East African Monetary union.

The Reality Check – Divergent Economies and Fiscal Constraints

The reality however is that monetary unions are not sustained by symbolism, rather they are sustained by economic synchronisation. In this regard, the economies within the EAC began to diverge rather than converge. Kenya faced inflationary pressures driven by global commodity shocks and domestic disruptions. Uganda’s fiscal deficits expanded as government expenditure continued to outpace revenue. Tanzania maintained relative currency stability through tighter controls, while Rwanda depended heavily on external financing to underwrite its long-term development strategy. These are not just marginal differences, rather they represent fundamentally distinct economic trajectories.

The primary convergence criteria were intended to harmonise these trajectories, with inflation capped at 8% , fiscal deficits including grants limited to 3%of GDP, and debt-to-GDP ratios maintained below 50% and a reserve cover of 4.5 months of imports. Only a limited number of member states have met these thresholds with any consistency over the past five years. Notably, Rwanda and Uganda maintained fiscal deficits within the 3% benchmark for a few consecutive years, in contrast to most other partner states. The onset of COVID-19 further complicated the landscape, increasing public debt burdens, weakening national currencies, and widening inflation differentials. For example, in Uganda, public debt rose substantially between fiscal years 2018/19 and 2019/20 as revenues collapsed and expenditure increased in response to the pandemic. Meanwhile, by 2023, several currencies including the Kenyan shilling, Rwandan franc, Tanzanian shilling and Ugandan shilling had depreciated against the US dollar, pressuring import costs and contributing to imported inflation. By the time the region began to recover from the impact, the prospect of fixing exchange rates within a single currency framework appeared less an avenue for deeper integration and more a source of significant economic risk.

Institutional Constraints and Comparative Lessons for Monetary Integration

Even if economic convergence were achieved, the institutional foundations necessary for a credible East African currency union remain underdeveloped. The EAMI is still only partially operational due to delays in staffing, inadequate resourcing, uneven legal harmonisation, and limited coordination of monetary and supervisory frameworks. Disputes over hosting arrangements, slow ratification of key protocols, and inconsistent political commitment have further impeded institutional consolidation.

Lessons from other regions illustrate that ambition alone does not sustain a currency union. The European Monetary Union emerged from the Maastricht Treaty, which enforced strict convergence criteria alongside a sequenced integration process that included the Single Market, capital account liberalisation, and the creation of institutions that eventually culminated in the European Central Bank. Crucially, Europe complemented monetary integration with mechanisms the EAC has not replicated, including fiscal stabilisation tools, a banking union with common supervisory standards, and shared debt instruments that function as shock absorbers. By contrast, the EAC has adopted convergence rules without the accompanying institutional architecture, resulting in a partial approximation of the European model. Similar challenges faced by the Economic Community of West African States(ECOWAS) in advancing the ‘Eco’ currency demonstrate that East Africa’s difficulties are not unique but reflect the structural and political complexities inherent in building any monetary union.

The New Reality – Fragmentation and Informal Integration

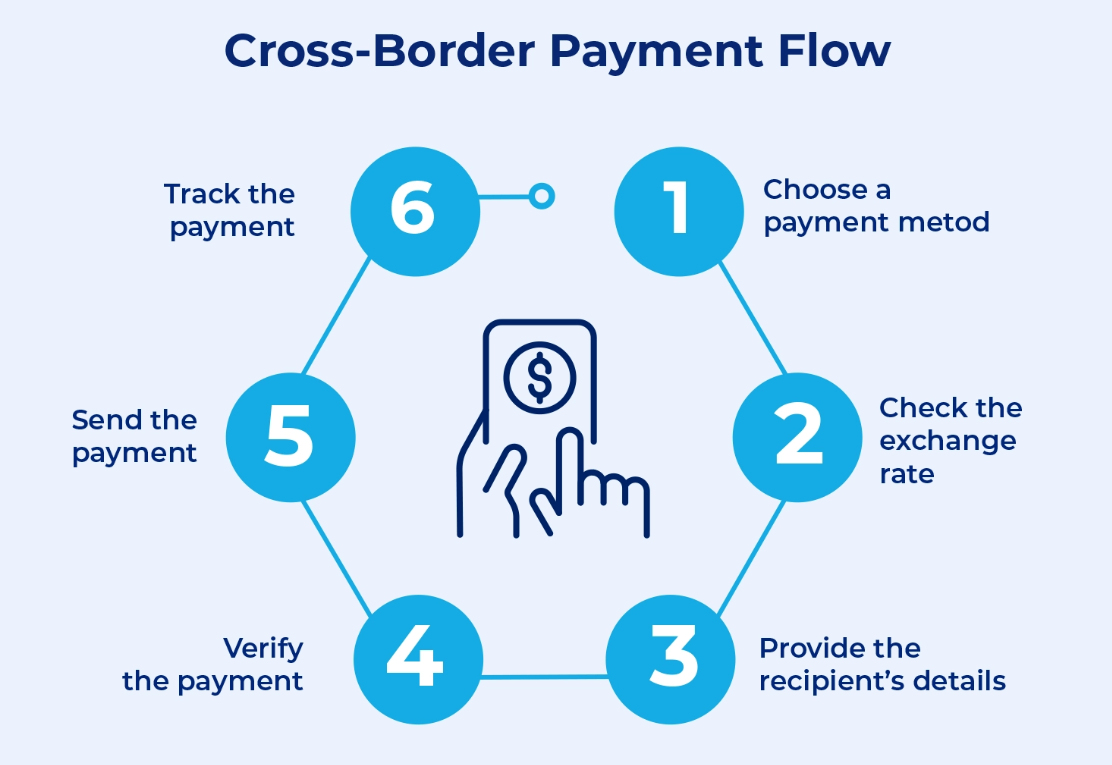

Although the formal political agenda for monetary integration has slowed, economic practices across the region point to a parallel and informal form of integration driven by digital finance. Cross-border mobile money transfers are expanding more rapidly than formal intra-EAC trade, and regional banks increasingly rely on internal clearing across subsidiaries to minimise currency conversion costs. Mobile money platforms such as MPesa, Airtel Money, and MoMo have evolved from national payment systems into regional financial networks that facilitate transactions for traders, transport operators, and small enterprises. In key border towns such as Busia, mobile money now functions as an informal settlement mechanism as transactions are conducted through digital wallets rather than physical currency.

Figure 2: Infographic on cross-border mobile money flows. Source

The Path Forward – Is a Monetary Union Still Feasible?

An EAC monetary union remains feasible, but the pathway is no longer as linear as envisioned in the protocol. Progress now depends on rebuilding credibility, strengthening institutions, and aligning political incentives before any consideration of issuing a common currency. The first priority is establishing the financial and regulatory infrastructure that enables monetary integration to function in practice, including interoperable payment systems, regional clearing and settlement platforms, harmonised supervisory frameworks, and stronger anti-money-laundering standards. As the Eurozone experience illustrates, such systems must be constructed long before a shared currency becomes operational.

Equally important is the transition from aspirational fiscal convergence to credible enforcement. Although the EAC has formal benchmarks, member states regularly exceed deficit and debt thresholds, underscoring the need for stronger peer review mechanisms, greater transparency in domestic borrowing, and consequences for persistent non-compliance. The final and most fundamental requirement is sustained political commitment to pooling monetary sovereignty. A viable union demands a willingness to transfer authority over monetary policy to a supranational institution. With meaningful progress on these fronts, a realistic timeline for integration could re-emerge.

Conclusion – A Union Delayed, Not Denied

The vision of an East African monetary union has always been a fundamentally political undertaking shaped by tensions between national priorities and regional commitments, and economic readiness and political will. The persistent delays reflect the reality that a shared currency requires far more than convergence on macroeconomic indicators or harmonised payment systems. The future of monetary union will depend not on stated deadlines but on concrete actions such as credible fiscal reform, stronger regional institutions, enhanced interoperability across financial systems, and sustained political commitment. These measures may lack immediate visibility and offer no shortcuts, but they form the essential groundwork for a viable and durable currency union.

In the end, the question is no longer why the EAC monetary union is not happening. More urgently, we must ask, what kind of union do East African states want and what are they willing to give to achieve it? If the region can align its interests as well as its aspirations, the promise of a single East African currency may yet move from vision to reality.