The Empty Chalkboard: How a Teacher Shortage Crisis is Shaping East Africa’s Future

Imagine a single teacher standing before a classroom not of 25, or even 40, but of nearly 60 young, eager faces. This is not an anomaly but a stark reality in many East African classrooms today, where the promise of education is being stretched to its breaking point. For decades, the region has grappled with the challenge of providing quality education for all, a mission powerfully advanced by landmark policies like Universal Primary Education. These initiatives successfully flung the school doors wide open, leading to a historic surge in student enrolments. Yet, this very success has cast a long shadow, exposing a critical and worsening deficit: a severe shortage of teachers. The teacher to student ratios in countries like Kenya, Rwanda, and Ethiopia are among the highest in the world, creating a pressure cooker environment where individualized attention is a luxury and quality learning is profoundly compromised.

This crisis matters now more than ever because the foundational cracks in the education system have been violently widened by the COVID-19 pandemic. The prolonged school closures did not just pause learning; they actively reversed it, eroding literacy and numeracy skills and pushing vulnerable children, especially girls, out of the school system permanently. As we stand at this critical juncture, the pre-existing teacher shortage has transformed from a chronic challenge into an acute emergency. Without a sufficient corps of qualified educators to provide the accelerated, targeted instruction needed for recovery, the learning losses from the pandemic risk becoming permanent. This perfect storm of overcrowded classrooms and pandemic fallout threatens to derail the educational prospects and future economic potential of an entire generation. The question is no longer if there is a crisis, but whether we can act in time to prevent it from becoming a catastrophe.

Current Trends and Scales

The teacher shortage in East Africa presents a complex picture of ambitious governmental initiatives struggling against deep seated structural and geographical disparities. The most prominent recent trend is the significant political commitment to large-scale teacher recruitment, exemplified by Kenya's pledge to hire 24,000 new teachers by January 2026. This effort is part of a broader three-year plan to employ 100,000 teachers, a direct response to the critical shortage.

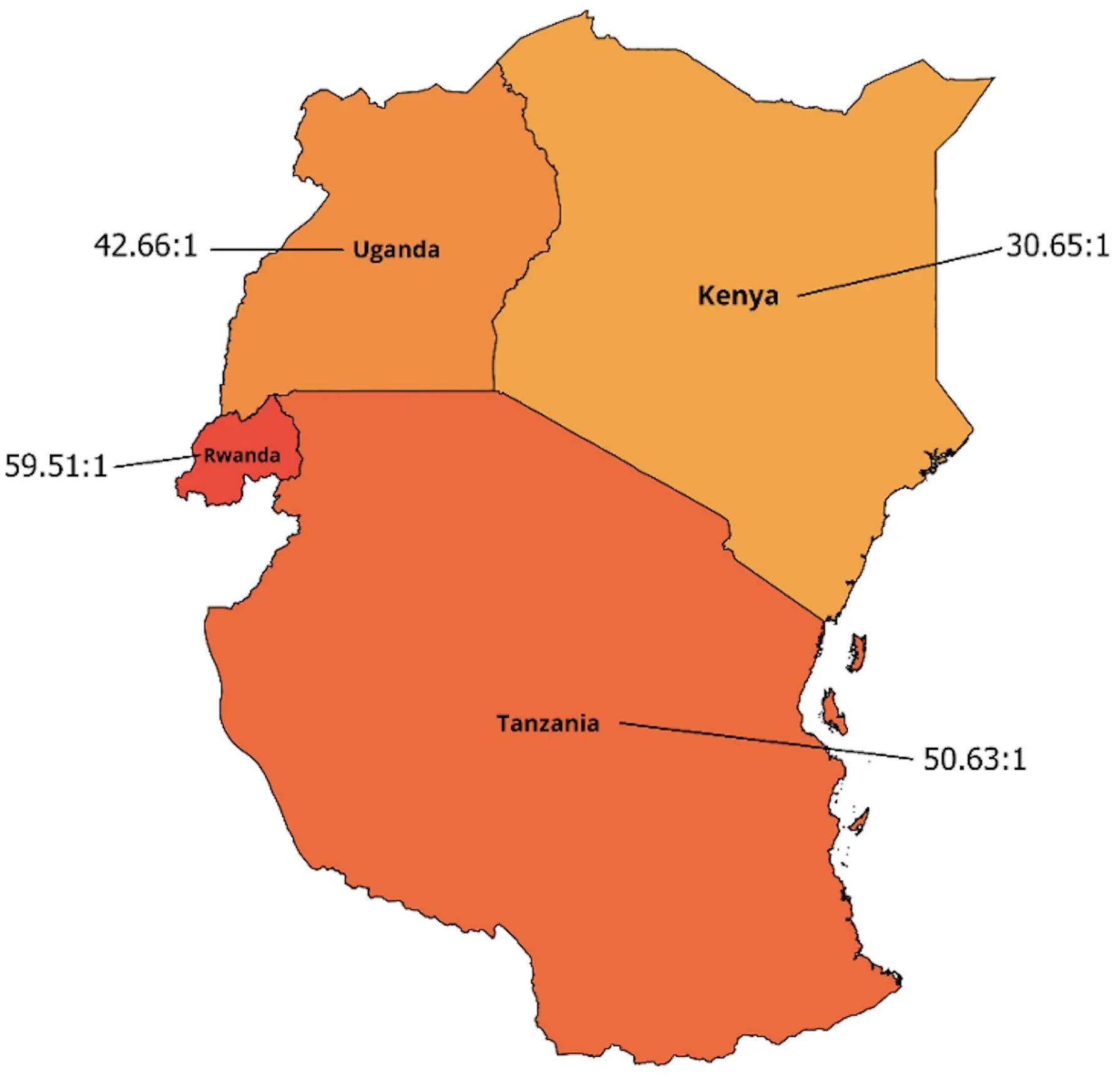

However, these national recruitment drives often mask the severe inequities in how the shortage is distributed. The crisis is unevennot uniform; it is disproportionately acute in remote and rural areas compared to urban centres. This geographical disparity creates a two-tiered education system. For instance, while Kenya grapples with a national pupil teacher ratio of 30.65:1, other East African nations face even more daunting statistics

Figure 1: National Student-to-Teacher Ratios in East Africa. Map by JEPA Africa. Data Source

These figures, all substantially higher than the global average of 24.26 student per teacher , highlight a regional crisis where classrooms are critically overcrowded.

Compounding the numerical deficit is a qualitative challenge in teacher retention and distribution. Higher teacher attrition rate, as a result of low salaries and poor working conditions, continuously drains the profession. This has led to a decline in the status of teaching, making it a ‘profession of last resort’ and exacerbating shortages in specialized subjects like mathematics and science. The result is a persistent gap between policy pledges and the on the ground reality, where the scale of the shortage continues to undermine educational quality for millions.

What Led to Teacher Shortage

The severe teacher shortage in East Africa is not the result of a single cause, but a complex interplay of chronic underfunding, poor working conditions, and systemic failures. At the heart of the crisis is the profound undervaluing of the teaching profession, manifested most clearly in chronically low salaries. In several sub-Saharan African countries, teacher compensation fails to lift educators above the poverty line, making the profession economically unsustainable. This financial strain is a primary driver of the ‘brain drain’, where the most qualified teachers leave for better paying opportunities.

Compounding the issue of low pay is the pervasive problem of low morale. Teachers are often posted to remote rural schools without adequate accommodation or teaching resources, leading to high attrition rates in the very areas where they are most needed. This dissatisfaction is fuelled by a sense of futility. Teachers report frustration when unrealistic curricula and poor learning conditions prevent them from seeing their students make progress.

Ultimately, these challenges are exacerbated by significant fiscal constraints. Governments, bound by budgetary limitations, often cannot afford to hire the thousands of qualified teachers who are already trained but unemployed. The financial gap is staggering; sub-Saharan Africa alone requires an additional $5.2 billion annually just to cover the salaries of the teachers needed. This chronic underinvestment creates a vicious cycle that perpetuates the very fiscal constraints that started it.

Solutions

Addressing the teacher shortage requires a multi-faceted approach, combining large scale international partnerships, grassroots initiatives, and technological innovation.

At the national and international level, a significant response is the launch of the Regional Teachers Initiative for Africa (RTIA), a major partnership between the European Union, UNESCO, and the African Union Commission. Backed by a €100 million budget, this six year program aims to tackle the shortage of 15 million qualified teachers in Sub Saharan Africa by 2030. The RTIA focuses on systemic change through technical assistance, innovative teacher training, and regional research. The RTIA's impact is already materializing through targeted funding for innovative teacher training and regional research partnerships. By generating and scaling effective practices, the initiative directly builds the region's capacity to close its vast teacher gap and improve educational outcomes.

Complementing these macro level efforts, non-governmental organizations are working at the community level to provide immediate relief. Organisations like PACEmaker International (PACE) address educational inequity and youth unemployment by recruiting and placing local teaching assistants in rural and slum schools. This model alleviates the burden on overstretched teachers and improves pupil-to-instructor ratios where state capacity is most stretched.

Simultaneously, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and EdTech platforms are emerging as tools to enhance teacher efficiency. In Kenya, teachers are using AI chatbots to automate time-consuming tasks like lesson planning, freeing up valuable time for direct student interaction. Start-ups like Kalasik and Nyansapo AI are developing tools tailored to the Kenyan curriculum, offering solutions from lesson planning to reading fluency assessment. However, the impact of these technologies is currently limited by a significant digital divide. With only 35% of schools having reliable internet access, AI remains an inaccessible solution for the majority. While not a substitute for more teachers, these technologies show promise as a force multiplier for existing educators.

Conclusion

The empty chalkboards and overcrowded classrooms across East Africa are more than just symbols of an education system under strain; they are a warning. The convergence of historic teacher shortages, pandemic induced learning loss, and deep-rooted systemic failures has created a generational crossroads. We have seen the scale of the crisis in the staggering pupil-to-teacher ratios, understood its origins in chronic underinvestment and poor working conditions, and surveyed the emerging solutions from the high-level ambitions of the RTIA to the community-based work of NGOs and the cautious integration of technology.

The takeaway is clear: there is no single fix. Bridging this gap requires a sustained, multi-pronged effort that matches the complexity of the problem itself. It demands that governments honour their recruitment pledges, that international partners provide steadfast support, and that innovations are deployed equitably. The future of millions of children and the economic trajectory of the entire region depends on the choices made today. To ignore this crisis is not merely to accept overcrowded classrooms; it is to accept the dimming of vast human potential. The time for action is now, before the chalk dust settles on an empty classroom for good.